Welcome to the first matchup of the week AND the last battle of the Saintly Sixteen. The first will be last, and the last will be first, apparently, and all that. Today we return to the ever-confusing Confusion Corner quadrant of the bracket as Isidora the Simple faces Catherine of Genoa. You'll recall that to get to this round, Isidora defeated Simeon the Holy Fool while Catherine took out her namesake from Bologna.

If you missed the results of Friday's fracas, Ives of Kermartin reached the Elate Eight by taking down Dunstan 67% to 33%.

And, since it's Monday, you'll want to keep refreshing your browser all day until Monday Madness miraculously shows up at some point. But in the meantime, go vote!

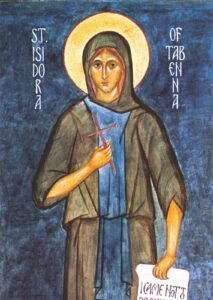

Isidora

In the fifth century CE, Lausus, chamberlain to Emperor Theodosius II of Byzantium, commissioned Palladius of Galatia to write a history of the Desert Fathers, which thankfully also happens to include some Desert Mothers in it. It is from Palladius’s account that we know the story of Isidora the Simple, who he calls, “The Nun who Feigned Madness.”

In the fifth century CE, Lausus, chamberlain to Emperor Theodosius II of Byzantium, commissioned Palladius of Galatia to write a history of the Desert Fathers, which thankfully also happens to include some Desert Mothers in it. It is from Palladius’s account that we know the story of Isidora the Simple, who he calls, “The Nun who Feigned Madness.”

This single anecdote is the only record we have of Isidora. The text of the Lausiac History reads, “In this monastery there was another virgin who feigned madness and possession by a demon.” Here he records how the other nuns despised her, refusing to eat with her, and that she willingly undertook the dirtiest and most strenuous labor, so that they called her, "the monastery sponge." Instead of a tonsure or cowl, like the other religious wore, she donned rags on her head. Palladius reports she satisfied herself with crumbs and the scrapings from the kitchen pots she washed. And although she was treated cruelly by the other nuns, “Never did she insult anyone nor grumble nor talk either little or much.”

It is only when the holy anchorite Piteroum seeks her out at the behest of an angel that Isidora’s true nature is revealed. He goes to the monastery of the Tabennesiot women, seeking a nun wearing a crown on her head, who he has been told is holier and better than him. When the nuns had presented themselves and still he hadn’t seen the one with the crown, he asked who was missing. They replied, "We have one within [who is] mentally afflicted.” Isidora did come when called, and “perhaps perceiving what was the matter, or even having had a revelation,” Palladius speculates she is intentionally ignoring the summons out of her humility.

When she finally meets him, he sees the rag on her forehead and falls to his knees, asking “Do you bless me?” Farcically, she also falls at his feet and asks, "Do you bless me, Master?" The nuns believe she is mocking or parroting him and call her sale, which means a holy fool. And Piteroum turns the insult on the women. "You are sale. For she is abbess to all of us.” The nuns, finally seeing Isidora for what she was—devout and humble, not possessed or deficient, confessed their cruelty toward her.

Isidora, “unable to bear her glory and the honor bestowed by the sisters, and burdened by their apologies,” left the monastery never to be seen again. In this simple story of Isidora, we see how even those committed to God can fail to understand true humility, yet when we truly see saintliness like Isidora’s, we can surrender our pride and repent.

Catherine of Genoa

“Lenten fasts make me feel better, stronger, and more active than ever.”

“Lenten fasts make me feel better, stronger, and more active than ever.”

So said Catherine of Genoa (1447 – 1510), and it is a fitting reflection for this season. Catherine’s spirituality was a deep and consuming mysticism – a personal connection to the Divine.

This deep, personal connection defined Catherine, as she put it: “My me is God nor do I recognize any other me except my God himself.”

This was not, for Catherine, a loss of self. Instead, it was an encounter with God’s love, a powerful and transforming force which became her guiding principle and source of meaning: “Love is a divine flame” and also “I shall never rest until I am hidden and enclosed in that divine heart wherein all created forms are lost, and, so lost, remain thereafter all divine; nothing else can satisfy true, pure, and simple love.”

Many a great mystic has written such words over the century while removed from daily life in a monastery or hermitage. But Catherine was immersed in the incarnate life – ministering to the sick in hospitals during the pandemics and plagues of 15th Century Italy. Reflecting on Catherine’s contribution to the world, in 2011 Benedict XVI said of her “the humble, faithful, and generous service in Pammatone Hospital that the Saint rendered throughout her life is a shining example of charity for all and encouragement, especially for women who, with their precious work enriched by their sensitivity and attention to the poorest and neediest, make a fundamental contribution to society and to the Church.”

Catherine applied her experience of God’s consuming love to the Medieval understanding of Purgatory. Rather than a land of fear and punishment, Catherine envisioned Purgatory as an even more personal encounter with the same powerful love she experienced:

“When God sees the Soul pure as it was in its origins, He tugs at it with a glance, draws it, and binds it to Himself with a fiery love that by itself could annihilate the immortal soul. In so acting, God so transforms the soul in Him that it knows nothing other than God; and He continues to draw it up into His fiery love until He restores it to that pure state from which it first issued.”

Even when it purifies and perfects, this love is not a source of fear but a joy and a motivation to living out our faith in the world. In Catherine’s words: “I find in myself by the grace of God a satisfaction without nourishment, a love without fear.”

With Catherine, may our Lenten fast lead us to encounter the Divine flame of God’s love, and drive us to a faith that is stronger and more active than ever.

[poll id="324"]

79 comments on “Isidora vs. Catherine of Genoa”

I voted for Catherine of Genoa, whose mystical experiences sound similar to the one such experience I have had, which occurred when I was working for the United Mission to Nepal. It has sustained me for almost 40 years.

Must one work in a hospital to be a saint? Must one be heroic? I voted for Isidore because I think “heroic” and “saintly” aren’t always the same. Isidore may have had a different IQ from the people around her, but it doesn’t make her devotion to service and humility any less saintly. Our votes are starting to indicate that we believe that unless you work at a hospital, you’re not a saint.

It does seem that we are passing forward heroic service providers during pandemics, and this preference for the "doers"--taking us back to Martha of Bethany and Florence Nightingale and the Martyrs of Memphis--has been a deep-seated trait of the LM pilgrim. Must one be a hero? Must one be a martyr? My hope is that the contemplatives and mystics will come to the fore and take their place at the table as welcome companions of the more "muscular" Christians. I would like to see Julian of Norwich win the Golden Halo. And of course Mr. Rogers will sweep. I hope we will see greater variety and embrace of spiritualities in the "golden circle." I'd like to see more Orthodox included, and a recognition of the "monophysite" tradition. But that requires accepting kontakia and popular accounts as sources of truth. I'm up for nominating a Druid tree for the lineup next year. Unless the Romans cut them all down. I would sic St. Guinefort on them; and then vote for him.

A Druid tree—I love it! I would vote for that in a heartbeat. I like your phrase “the “more muscular Christians”!

Isadora pretended to be a fool until she was one, just because she scrubbed pots & did what the other nuns didn’t want to do. That makes them lazy & privileged. Cannot vote for pretender no matter how good.

Catherine had me at “a personal relationship with God” which is something I believe we all should have & we sure could use her skills during our own pandemic.

I VOTE FOR CATHERINE OF GENOA. SHE HAD MORE WORDS THAN ISADORE,

WHO WAS A CLOSE SECOND.

In Isidora's story I see the Cinderella story. The wicked stepsisters presenting themselves to the Prince, and Isidora, the Monastery sponge, finally being summoned and discovered. I'm voting against my bracket by supporting Catherine's advancement. Hers is a more documented life, rather than a fairytale.

Sorry, folks. These just something about Isadora that spoke to me. She's got my vote.

Catherine of Genoa is amazing and I am grateful for her writings and mystical insights. However, I too am drawn to vote for Isidora today. Such a delightful weirdo -- I mean that in the best possible way. A delightful weirdo, beloved of God. Who needs the rest of 'em? You go, girl! And she did.

For those who compare Isidora's life to the "fairy tale" of Cinderella -- "Fairy tales" /Folk tales are stories that give satisfaction to their listeners. The enduring themes in her story -- her humility, her perseverance under persecution and terrible conditions, the way people judge her based on appearances, and especially her inner nobility that the others in their arrogance dare to overlook -- this life is, to me, a parable illustrating the source of worth -- is a person's worth based on their rank? their appearance? or their service to others? The part that troubles me in this story is not that Isidora exhibited a different set of behaviors (whether or not she was neuroatypical) but the ending of the story where she vanished never to be seen again -- almost as though she was "too good for this world, too pure." I ended up voting for Catherine of Genoa, because she too was an exemplar of service; although she said she wanted to be annihilated in God, she did not vanish after being recognized. So I chose the Woman who Lived.

I would like to remind everyone that Isidora's behavior being labeled as "feigning madness" or "being possessed by a demon" was a supposition by a man who met her briefly in an age where any odd, erratic, or unusual behavior, especially displayed by a woman, was immediately condemned as madness, hysteria, demonic possession, etc. Psychological history illustrates centuries of cruel, inhumane, demoralizing, and misguided attitudes and behaviors toward those who suffered from what we now know truly to be mental illness often stemming from trauma (psychological and/or physical) and congenital/hereditary disorders. A person suffering from a mental illness at that time would have faced struggles and persecution that are incomprehensible for us today. I think, based on what little we know of Isidora, it is unfair to assume and label her as a person who intentionally "played dumb" to provoke the other nuns and cause them to sin. I believe a person who would do such a thing would not purposefully choose the hardest, dirtiest, and "lowliest" tasks and living conditions to make a point. We will likely never know her entire story, but from the story that has been told to us, Isidora appears to be a Godly, humble, prayerful servant of the Lord who simply wished to serve others as Christ has taught each of us to do. She gets my deep respect, compassion, and honor alongside my vote.

Well said!

Far from being "simple" or even "holy," Isidora was an insidious deep-cover terrorist. Her name "Isidora" ("It was Greek to me." Spoken by Casca in Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar") means "Gift of Isis." Isn't ISIS that bunch of bad guys?

The terrorist organization ISIS was started in 1999 and became well known after 9/11. I'm sure this is a troll post, but please do not spark this kind of negativity and conflict about a poor nun from the 5th century that we know next to nothing about. We are talking about a saint during Lent approaching Holy Week. Show some respect and decorum, please.

Thank you. LM attracts a few trolls from time to time. Saint Spyridon, cast out all demons.

It is much worse than you think. Isis has appropriated not only a holy woman from late antiquity, but also a New Orleans Mardi Gras organization, the all-female Krewe of Isis. Covid squelched their parade this year, but, emulating Arnold the Governator, "They'll be back." https://www.kreweofisis.org/all-about-isis Isidora is in good company, however, with her male namesake, St. Isidore of Seville, patron saint of the Internet. https://gizmodo.com/the-patron-saint-of-the-internet-is-isidore-of-seville-1595023500

Sancta Isidora et Sancte Isidore, orate pro nobis!

And thanks for the name of the patron saint of the Internet! I've been wondering about that for years. Now I'll have to find a little statue or picture of him to put on my computer. I wonder if

St. Isadore will protect us from hacking.

It did strike me as a little odd (almost humorous) that a severe monotheistic group would choose a name that turned out to be (in English, anyway) the name of a very important Egyptian goddess.

Catherine of Genoa

All-encompassing care

Tremendously longing to rest in the

Heart of God

Engaging the indigent

Rehabilitating with love

In all things

Never giving up, never giving over to fear

Enfolded in the eternal love of God

(St. Mark's Friends, ABQ NM)