Who's ready for a full week of madcap Saintly Sixteen action? Well, ready or not, it's coming your way as Lent Madness 2021 continues in earnest.

Today it's Egeria vs. Arnulf of Metz as they vie for a shot at the Elate Eight. To get here, Egeria made it past Tarcisius while Arnulf took down Vincent of Saragossa.

If you missed Friday's result, Catherine Booth marched past Constantine 70% to 30%. Go vote!

Egeria

Egeria—pilgrim, writer, journalist, and popularizer of the definite article—sent letters back to her community in Spain throughout her travels in the late 4th century.

Egeria—pilgrim, writer, journalist, and popularizer of the definite article—sent letters back to her community in Spain throughout her travels in the late 4th century.

Her writings are easily available today for our perusal and appreciation—so it might be surprising to learn that the fragments we have were not translated into English until 2005. (Earlier fragments were referenced in other works, and it was partially translated as early as the end of the 1800s, but by and large, the thoughts of a world-travelling religious woman were not widely considered important until relatively recently. Our loss.)

According to academics, her writing style was not polished: she misspells words and does not appear educated. But she wrote the way she talked, and so her writing gives us an insight into what a fourth century traveller thought and cared about—the way her mind worked. Recent translations work hard to preserve the loose, breezy way she wrote, and her voice. (The recently-released edition from Liturgical Press is very good.)

Egeria appears to be the subject of a letter written by a Spanish monk in the late 7th century named Valerius to his fellow monks. He seems to honestly be impressed with Egeria, though that can be hard to discern, amidst his general issues with women. Throughout the letter, he spells her name four different ways (bless his heart). He describes her as a virtuous, faithful Christian, even though she was in the form of a “weak woman”(!), and hopes all the monks back at home will emulate her. He proclaims that all the local saints in his region loved Egeria, and that he was sure that “she will return to that very place where in this life she walked as a pilgrim.”

It’s worth noting Egeria’s casual mention of armed escorts at various places in her letters. Pilgrimages were extremely dangerous in the late 4th century, and it wasn’t rare for thieves to waylay travelers on isolated roads. It is also remarkable that Egeria mentions, on the one hand, “helpful Roman soldiers who assist us in the name of public safety” and—on the other hand—meeting with confessor bishops while on her journeys. “Confessor” was a title used by local Christians to refer to someone who had been arrested and tortured, but not martyred, for their faith by Rome. In the 380s, those who had lived through the last Roman persecutions were still in church leadership—albeit fewer and fewer in number. Egeria is basically chronicling the change between a persecuted church and a church that can run the world.

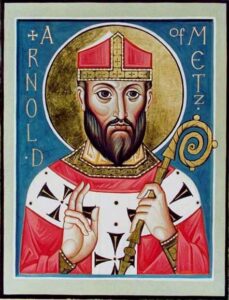

Arnulf of Metz

While in this century, Arnulf (Arnold) of Metz is best known by his association with beer and breweries, in his own time he was renowned for his deep pastoral care and compassion for the people entrusted to his oversight.

While in this century, Arnulf (Arnold) of Metz is best known by his association with beer and breweries, in his own time he was renowned for his deep pastoral care and compassion for the people entrusted to his oversight.

Arnulf was born into wealth and privilege – a condition which can predispose one to a sense of entitlement. But Arnulf went in the other direction. At every opportunity he used what he had for the good of others.

His hometown of Metz became a destination for the poor, vulnerable, and destitute of the kingdom, who trusted so much in the Bishop’s generosity that they travelled great distances to be in his presence. And once they were, Arnulf would put his own clothes on these travelling beggars, give them food and water from his own table, and follow the Lord’s example by washing their feet.

Once, Arnulf is remembered as saying “Don’t drink the water, drink the beer.” This too was a pastoral concern. The brewing process meant that the beer was safer to drink than the local water supply. In a time of pandemic and disease, Arnulf relied on the wisdom of experience to direct his parishioners to the best practices to preserve their own health and the well-being of the community.

Similarly, Arnulf stood between the people of Metz and destruction when a fire broke out in the town. As a fire in the palace threatened to spread through the town, causing untold destruction, Arnulf said “If God wants me to be consumed, I am in His hands.” He stood in front of the fire, and making the sign of the cross commanded the fire to abate – and it did.

Beyond these powerful stories, Arnulf found ways to fight for the people even in the mundane work of ecclesial and political administration. Arnulf had his hand in the formation of the Edict of Paris (615), which has been compared to the Magna Carta. Among the laws enacted by the Edict was a change that demanded that bishops be elected by the people, rather than appointed by kings.

The legacy of Arnulf is of ecclesial and pastoral authority that is consistently working for the good of God’s people in all things.

[poll id="319"]

90 comments on “Egeria vs. Arnulf of Metz”

I arrived late today, cast my vote for Egeria and was horrified to discover she was so far behind. Last year our churches in the UK were locked over Holy Week and Easter. For the first time in years I wasn't able to participate in the mysteries of Christ's final days, his arrest, trial, death and resurrection with the community of faith. We did our best at home, but it brought home to me anew how much we owe to Egeria's faithful witness, her courage and cheerfulness. Next time Egeria ...