In the last battle of the week -- and the penultimate matchup of the Saintly Sixteen -- Ives of Kermartin faces Dunstan. To get here, Ives beat Jacapone da Todi while Dunstan took out Maryam of Qidun.

In a hotly contested battle yesterday, Absalom Jones snuck past Marianne Cope 52% to 48% to snag a spot in the Elate Eight, where he'll face Catherine Booth. See? These matchups only get harder and harder.

We'll be back first thing Monday morning to finish up this round and then, on Tuesday, things get serious (or not so serious, as the case may be) as we commence the Elate Eight.

Ives of Kermartin

St. Ives, a 13th century French lawyer and clergyman, applied his knowledge, his sense of fairness, and his deep spirituality to helping the poor and under-represented.

St. Ives, a 13th century French lawyer and clergyman, applied his knowledge, his sense of fairness, and his deep spirituality to helping the poor and under-represented.

His life’s work and dedication earned him well-deserved monikers: Advocate of the Poor, Defender of Widows, Ideal of the Legal Profession, and Patron Saint of Attorneys.

He lived a spartan life, abstaining from eating meat and drinking wine. A friend noted, "I have seen him at table in my mother's house, and he never partook of fish or flesh or wine, and he always wore poor garments, though he had a good income both from his own estate and from his church office."

Ives donated his salary to the poor, never accepting gifts or bribes, which was a common practice in his day. He was known to settle disputes out of court to avoid additional fees.

Ives’ actions illustrate his compassion. He helped resolve a deep dispute between a mother and her son by offering Mass for them, which led to an amicable agreement.

He uncovered a scheme by two men to cheat a poor widow of all she possessed. "Have no fear," Ives told her. "If you are in the right, I shall defend you, and with God's help we will prevail." He cleverly proved her innocence while the judge punished the guilty.

There were 100 examples of his holiness following his 1303 death. In one, a woman was robbed. She prayed to Ives at his tomb, then heard the names of the robbers. Justice, through Ives, was served.

In 1362, the mystic Jeanne-Marie de Maillé told of a vision of Yves in which he said, “If you are willing to abandon the world, you will taste here on earth the joys of heaven."

He was known to fast throughout his university years and beyond, which may have contributed to his death. He was buried in Tréguier in Northwestern France in the church he founded. Etched on his tomb:

Sanctus Ivo erat Brito

Advocatus et non latro

Res miranda populo

St Ivo was a Breton,

A lawyer and not a thief;

A wonderful thing for the people to set eyes on

Pope John Paul II issued a message about Ives in 2003: “St. Ivo was involved in defending the principles of justice and equity. He was careful to guarantee the fundamental rights of the person, respect for his primary and transcendent dignity, and the protection that the law must guarantee him. For all who exercise a legal profession, whose patron saint he is, he remains the voice of justice, which is ordained to reconciliation and peace in order to create new relations among individuals and communities and build a more impartial society.”

Dunstan

St. Dunstan is remembered as Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, London, and Finally Archbishop of Canterbury, and in particular for his revival of monastic life in England following the Viking invasions of the 8th century.

St. Dunstan is remembered as Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, London, and Finally Archbishop of Canterbury, and in particular for his revival of monastic life in England following the Viking invasions of the 8th century.

As a boy, Dunstan trained with Irish monks in the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey; he was noted even as a child for his enthusiasm for learning, and his artistic abilities and mastery of many different media – including as a silversmith and a scribe – skills which would later become bedrocks of his life as a monk. Artistry requires vision of what can be, not limitation by what is in front of you at present – Dunstan’s vision, developed through craft, aided his work in creating a vision for the restoration of Glastonbury.

In his youth, Dunstan was called into the court of King Athelstan, King of the Anglo-Saxons; he quickly became a court favorite, which led to (fully predictable) palace intrigue. Other courtiers wanted to disgrace Dunstan, so he was accused of witchcraft and black magic; the plot succeeded and he was forced to leave. As he left, he was attacked by his enemies and left in a cesspool to die. His unlikely survival almost certainly assured the later revival of English Monasticism under his vision.

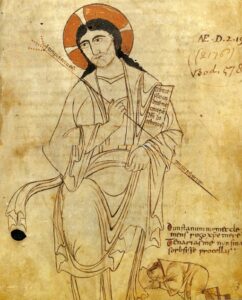

At Glastonbury, Dunstan continued to pursue his artistry; he is considered the likely artist of an image of Christ with a small, kneeling monk beside him in the Glastonbury Classbook – the text in the image reads: “Dunstanum memet clemens rogo Christe tuere, Tenarias me non sinas sorbsisse procellas” – “Remember, I beg you, merciful Christ, to protect Dunstan, and do not permit the storms of the underworld to swallow me up.”

Folk legend recalls that one night while forging metal, Dunstan was tempted by the devil in the form of a beautiful woman, only for Dunstan to defeat the Devil by seizing its nose with his red-hot tongs. The story is recalled often in English literature, including by Charles Dickens in A Christmas Carol, and in one other particularly memorable folk rhyme:

St. Dunstan, as the story goes, /

Once pull'd the devil by the nose /

With red-hot tongs, which made him roar, /

That he was heard three miles or more.

As a Bishop and Archbishop, Dunstan was lauded for his statesmanship, his diplomatic tact most likely developed over years of being at the heel end of palace intrigue in his younger days. After a long career of service to the church, Dunstan is reputed to have had these final words: “"He hath made a remembrance of his wonderful works, being a merciful and gracious Lord: He hath given food to them that fear Him."

[poll id="323"]