Today's matchup covers a lot of territory. From Spain to Haiti to Germany to New York to Hawaii, Bartolomé de Las Casas and Marianne Cope were collectively well traveled (remember travel?).

Yesterday, Euphrosyne left Evagrius the Solitary basically standing alone on a street corner for the rest of Lent 64% to 36%. Though, in fairness, that's probably Evagrius' happy place.

Oh, and if you missed yesterday's rousing edition of Monday Madness with Tim and Scott, you can watch it here.

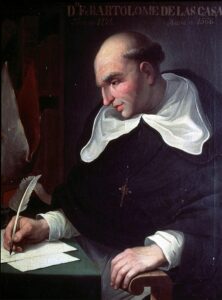

Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas was not impressed.

Bartolomé de las Casas was not impressed.

Dominican friar Antonio Montesinos had given an impassioned speech, which historian Justo L. González describes in the first volume of The Story of Christianity as the first open protest against the exploitation of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Montesinos had declared that colonizers were in mortal sin because of their “cruelty and oppression” of the people.

But Montesinos’s speech did not sway las Casas. Las Casas owned what was called an encomienda, which included both land and the Indigenous people who lived there. The people were forced to work for him in exchange for his “guidance,” which included “civilizing” them and teaching them Christian doctrine.

Las Casas was born in 1484 in Seville, Spain, and later settled on the island that now is Haiti and the Dominican Republic, where it’s possible he was the first priest ordained in the so-called New World. He’d been in Santo Domingo for nearly ten years when he heard Montesinos preach. It would be three more years before las Casas had a radical change of heart at Pentecost about the treatment of Indigenous peoples. He gave up his encomienda and preached that others should do the same.

It would be years yet before he’d realize the same rights extended to enslaved peoples from Africa. “All the peoples of the world are humans, and there is only one definition of all humans and of each one, that is that they are rational,” he said. “Thus, all the races of humankind are one.”

Las Casas spent the rest of his life advocating for Indigenous peoples, arguing that the way colonizers had exploited them was incompatible with Christian faith. This included lobbying for legislation protecting Indigenous people in Spain. He also wrote a number of books detailing the atrocities he’d witnessed, which led many people to question the morality of the whole colonial enterprise.

Las Casas died in 1566. Today, he is remembered as a predecessor of the liberation theology movement and an early advocate for human rights. He reminds us to keep learning, repenting, advocating, and doing better.

Collect for Bartolomé de las Casas

Eternal God, we give you thanks for the witness of Bartolomé de las Casas, whose deep love for your people caused him to refuse absolution to those who would not free their Indian slaves. Help us, inspired by his example, to work and pray for the freeing of all enslaved people of our world, for the sake of Jesus Christ our Redeemer, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Marianne Cope

Marianne Cope was an American nun who established hospitals throughout central New York and Hawaii.

Marianne Cope was an American nun who established hospitals throughout central New York and Hawaii.

Born Maria Anna in Germany in 1838, her family emigrated to Utica, New York before her first birthday. They took up residence within the parish of St. Joseph, and the children attended the local Catholic school. Because Maria Anna’s father was sickly and unable to work, she dropped out of school and went to work in a factory after the eighth grade. Once her younger siblings became old enough to support themselves, Maria Anne pursued her dream of a religious life. She entered a Third Order Franciscan community in Syracuse, New York in 1862, changing her name to Marianne.

Once an official nun, Marianne became a teacher and quickly advanced, becoming the principal and then the head of her religious congregation by 1870. She helped to found two hospitals in central New York—insisting each time that medical care be offered to all comers, regardless of religion or creed (unusual for the time.). She became the superior general of the first public hospital in Syracuse and helped relocate the Geneva Medical College of Hobart College, where it became the medical school of Syracuse University.

In 1883, the king of Hawaii asked her to come and work with the lepers in Hawaii. More than fifty other congregations had already said no, but Marianne jumped at the chance. She landed in Hawaii in 1883 and set up a triage hospital for treatment of leprosy. She intended to spend only a few years in Hawaii, but she ended up serving there for the rest of her life, building hospitals and schools in the islands. She built a women’s hospital in Maui (the first hospital on the island) and opened a home for the children of leprosy patients—children who had become homeless because of their association with such a dreaded disease. When Fr. Damien of Molokai, well-known for his work in the leper colony, developed the disease, she took care of him, and when he died, she took charge of his work in addition to the hospitals and schools she was already running.

Marianne died in 1918 and became one of only a few American women to be canonized by the Vatican.

Collect for Marianne Cope

Bind up the wounds of your children, O God, and help us to be bold and loving in service to all who are shunned for the diseases they suffer, following the example of your servant Marianne, that your grace may be poured forth upon all; through Jesus Christ our Lord; who with you and the Holy Spirit lives and reigns, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

[poll id="310"]