Margaret of Scotland

Saint Margaret of Scotland was a noblewoman who contributed lasting gifts to Christians. She was known by various names; she was the mother of a far-reaching family; and she was the subject of biographies, scholarly books, and historical fiction.

Saint Margaret of Scotland was a noblewoman who contributed lasting gifts to Christians. She was known by various names; she was the mother of a far-reaching family; and she was the subject of biographies, scholarly books, and historical fiction.

She is Scotland's only royal saint. Among her monikers are Queen Margaret of Scotland, aka Margaret of Wessex, aka "The Pearl of Scotland" aka Saint Margaret.

She boasted quite a pedigree. Saint Margaret of Scotland was the daughter of King Edward the Exile. She was married to King Malcom III of Scotland, and was the mother of what today might be considered an overachieving family - three kings, one queen, a countess, a duke, and a major landowner: King Edgar of Scotland; King Alexander of Scotland; King David I of Scotland; Queen Matilda of England; Edmund, Bishop of Dunkeld in Scotland; Mary, Countess of Boulogne in France; and Etherlred, who owned extensive lands on both sides of the Firth of Forth. Also, let’s not forget her oldest son Edward who died in battle with her husband, King Malcom, immortalized in Shakespeare’s celebrated play, Macbeth, aka the Scottish Play.

A miracle attributed to her stems from her Gospel Book that was decorated with many jewels. According to legend, the jeweled book was dropped in a river, and, as the legend goes, the book was miraculously recovered. That same Gospel Book is currently located in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, one of the oldest libraries in Europe.

Saint Margaret is the subject of numerous historical novels, biographies and books, starting with the Life of St. Margaret, written by her confessor, Turgot, not long after her death in 1093, up to 2010’s Queen Hereafter: A Novel of Margaret of Scotland by Susan Fraser King. There are also a series of books about her and her husband.

The legacy of Saint Margaret continued after her death when, in 1560, Mary Queen of Scots had custody of Margaret's head. Mary believed that Margaret’s head, considered a relic, would assist in childbirth. Later, Margaret’s head landed with the Jesuits at the Scots' College, Douai, France, but evidently was misplaced or mislaid during the French Revolution. Therefore, like many others, Margaret’s head was lost in the French Revolution.

Among the many churches worldwide named in her honor is St. Margaret's Chapel in Edinburgh Castle in Edinburgh, Scotland, established by her son King David I.

However, when it comes to Lent, Saint Margaret of Scotland remains the true Patron Saint of Lent Madness, since she insisted that clergy begin Lent on Ash Wednesday (not unlike our Saintly Smackdown).

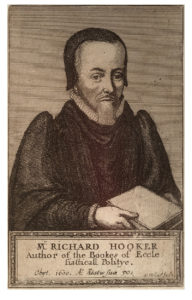

Richard Hooker

Richard Hooker was born during the reign of Mary I, Queen of England after the death of her half-brother Edward VI, and died four years prior to the Hampton Court Conference. As such, he came of age in and became a leader of the Church of England during a time of incredible transformation. Protestants and Roman Catholics were fighting one another, and the soul of the Church was in danger of being torn asunder by the conflict. He is a saint worthy of remembrance particularly in a time of fierce division.

Richard Hooker was born during the reign of Mary I, Queen of England after the death of her half-brother Edward VI, and died four years prior to the Hampton Court Conference. As such, he came of age in and became a leader of the Church of England during a time of incredible transformation. Protestants and Roman Catholics were fighting one another, and the soul of the Church was in danger of being torn asunder by the conflict. He is a saint worthy of remembrance particularly in a time of fierce division.

Richard Hooker stepped into the melee between Protestants and Roman Catholics and appealed to reason and tolerance, suggesting that Christians in conflict should consider more of what we have in common over that which separates us. To quote him, “God is no captious sophister, eager to trip us up whenever we say amiss, but a courteous tutor, ready to amend what, in our weakness or our ignorance, we say ill, and to make the most of what we say aright.”

After his royal appointment as Master of the Temple Church in 1585, Hooker came into conflict with Walter Travers, a Puritan who was angry because, among other things, a previous sermon by Hooker argued that salvation wasn’t dependent on our grasp of God’s grace. This argument suggests that, at least in theory, salvation is open to all, including (cue the dramatic music) Roman Catholics. In the midst of this dispute, Hooker began writing Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, a defense of the Book of Common Prayer and critique of Puritanism. It is in Laws that Richard Hooker argues a theology of the Eucharist that goes beyond Christ’s presence in the bread and wine and argues Christ’s presence in the ones receiving the Sacrament. For Hooker, an argument about the presence of Christ in the elements of the Eucharist is pointless if one does not also consider the presence of Christ in the recipient because, by participating in the Eucharist, we participate in the Incarnation. One surprising advocate of Laws was Pope Clement VIII, who described it as possessing “seeds of eternity.”

When confronted with the “Vestiarian Controversy” which questioned the merits of clergy wearing the clerical cap and surplice, Hooker, clearly weary of the verbosity and lack of Christian charity with which Christians engaged with one another, wrote that “There will come a time when three words uttered with charity and meekness shall receive a far more blessed reward than three thousand volumes written with disdainful sharpness of wit.” To be honest, though written 450 years ago, those are words still bear relevance for our current context.

[poll id="222"]